My Art of Teaching

"If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail" - Abraham Maslow

A teacher transfers knowledge with effect and affect. We improve our techniques for optimal effect. We innovate our teaching environment/incubator to affect learning. Teachers should embrace lifelong learning themselves for regular recall of this process.

Classroom Teaching

I have taught a continuum of learner levels. My efforts tend to our less privileged populations.

- Urban Middle School: Sheridan MS (now converted to K-8)

- Urban High School: Career HS (Yale Scholar Program)

- Urban Community College Teaching: Gateway CC

- Undergraduate Teaching: University of Minnesota, University of Tennessee, University of Illinois at Chicago, University of Connecticut at Stamford.

- Post-Graduate Teaching: University of Illinois at Chicago, Yale School of Medicine.

I carry two principles across this spectrum.

First, if we fail to convey the message to your students that you care about them, we will not be very successful.

Second, we show the basics and guide the students to teach themselves. Science is a venue and a tool to develop critical thinking and the process of gathering information to solve problems. We show pupils how to plan, to complete, and to succeed with tasks and goals.

A science teacher is not there to propagate science clones, but to train young people to make their small successes, moving them further down their own path of choosing. Transference of your own passion and successes in science can stimulate their choice to follow the route. We must resist the temptation to count success by the ability to clone oneself in our teaching incubator.

To carry out these goals, we must know the classroom in front of you. We must then stay as close as possible to the pulse of classroom and students. Constant monitoring, adapting and adjusting to where the pupils are is critical to finding creative ways to lead them to where you expect them to be. We don't lower our expectation, but lead students to our standard.

A teacher must develop different techniques and pedagogies to load into the teaching toolbox. "If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail," as said by Abraham Maslow. We use various styles in a sequence depending on the tempo and needs of the classroom. Explain to the students what you are doing and why you are doing it. Students can be very forgiving of mistakes if they already know you care and are doing your best.

Innovation in Education

At the college level, I believe in innovating educational programs to give students self-empowerment.

One such program is the Biology Colloquium at the University of Minnesota. Students protested the administration in the late 1970s. They demanded a course run by themselves and for themselves. They designed a self-containing course with their social emphasis. This program had a good run. It was in decline and under the budget ax in 1985. The famed ornithologist David Parmelee recruited me and unleashed this energetic undergraduate to revitalize and restructure this dying program.

The program became a jewel of the university for many decades. It is still operational to date. This idea mushroomed many other programs that engage students in leadership training, practical science and career learning. It is team learning in its purest form.

We built a tailored program in Chicago. It transforms biological education at this urban campus so rich with diversity.

I learned early that a good idea needs a structural framework for self-renewal and longevity.

- “Major Commitment to Biology Majors”. By Andrew Gottesman, Chicago Tribune, April 18, 1993

- “Students in a Class of Their Own”. UIC News, April 14, 1993

- “Ngô Builds, Spreads Colloquium Concepts”. University of Minnesota CBS Alumni News, Fall 1996

At the graduate school level, I believe in multidisciplinary training to prepare young professionals with an ability to adapt to the moving world and then to move the world.

In 1998 I co-founded the Yale Biotech Special Interest Group at Yale University. We brought together students of Yale Law, Medicine, Life Sciences and Business Schools. It is a program run by the students for the students, bridging the gap between academia and industry. The program provides transfer learning in applied science and business management.

We were at the right time when Yale and New Haven started their biotechnology thrust. It became an overnight success. The concept integrated into the Yale curriculum.

I learned that a good idea would grow faster in fertile ground and with the right timing.

- “Yale Biotechnology Student Interest Group Hosts Reception on the Commercialization of Biomedical Technologies”. YaleNews, September 9, 2002.

At the K-12 level, I believe in the proverb "It takes a village to raise a child” for our urban settings of fragmented homes and high economic stress.

We built a model STEMM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics, Medicine) program for an urban middle school. We designed a NASA Explorer School in Connecticut. I teamed with parents, teachers and administrators. We forged partnerships with organizations and industries at city, state and national levels.

The common goal for stakeholders was to prepare our middle-schoolers to grow up as productive members of society. For some students, we aspired them to go into STEMM careers.

Our Explorer School became a top program in the national NASA network. We succeeded short-term, but I failed with my goal of longevity. The quality of the program fell off after my departure.

I learned that a good idea in harsher soil needs a longer period of soil revitalization before transitioning to sustainability.

- "Fast Track to Teaching - States design high-speed routes for scientists to run classroom", Howard Hughes Medical Institute Bulletin, March 2003, Vol 16: 4-5.

- “Program Teams Yale Scientists, Middle School Students”, Yale Bulletin and Calendar, March 28, 2003, Volume 31, Number 23.

- “Yalies Pitch In At Science Fair”, Yale Daily News, February 7, 2003

- “Dr. Ngô Passion For Teaching Science Is Contagious”, New Haven Register, April 10, 2003.

- “Sheridan Chosen as 1st NASA Explorer School in State” New Haven Register, June 12, 2003

- “The NASA Education Enterprise: Inspiring the Next Generation of Explorers”. National Aeronautics and Space Administration Website.

- “Dr. Ngo’s Students Say ‘Yes’ to Science”. Hartford Courant, October 4, 2003, page A1.

- “Ngô evolves from researcher to Elm City teacher”, Yale Daily News, December 4, 2003, p. A1z

- “Marsapalooza: An Out-of-This-World “Opportunity" to Inspire the Next Generation of Explorers.” National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

- “Local Students Visit EPH Labs” Yale University School of Public Health Website, March 2004.

- “Sheridan School Students Look Into Space Through Eyes of Astronaut”, New Haven Register, April 9, 2004, page A3

- “NASA’s a Blast at Sheridan”, Yale Daily News, April 4, 2004, page 5

- “More Visits to Goddard Explorer Schools; Education is the Key”. NASA Goddard News, April 2004, Vol. 1, Issue 4.

- “Sky is no longer the limit at NASA Explorer Schools”, Ocean to Orbit, Hamilton Sundstrand Quarterly Publication, January 2005

- “Sheridan-NASA call out of this world”, New Haven Register, April 1, 2005.

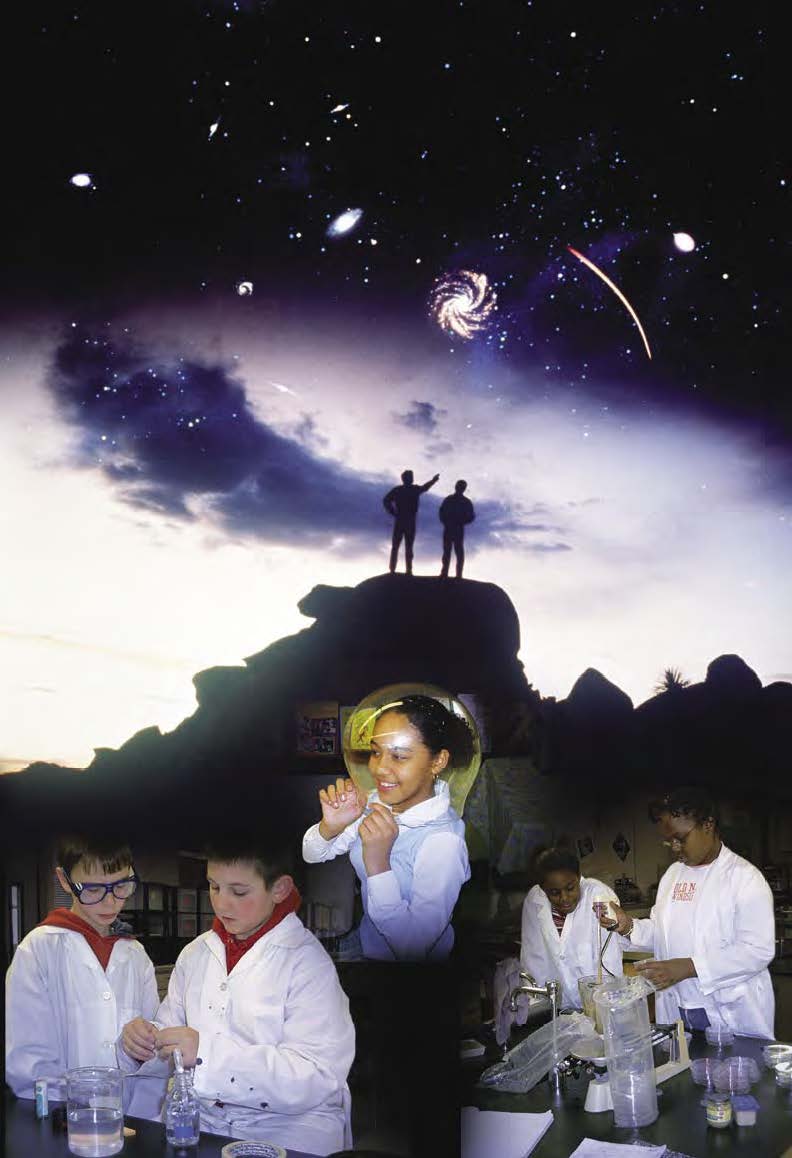

Photos. NASA Explorer School, Sheridan Middle School, New Haven, Connecticut.

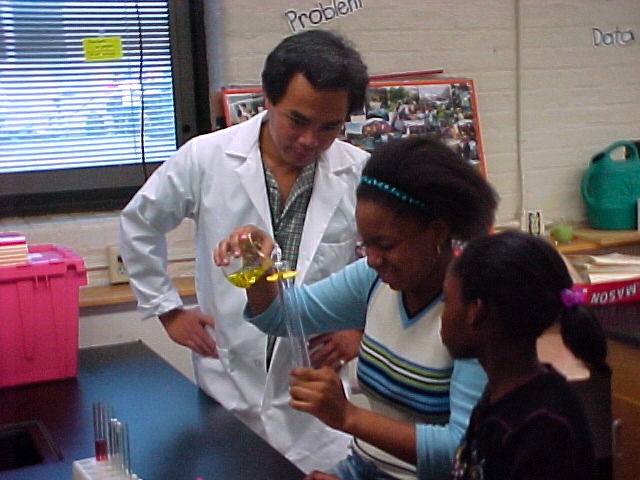

Photos. NASA Explorer School, Sheridan Middle School, New Haven, Connecticut.